Design for User Experience

During the Fall 2016 semester, I taught Design for User Experience at Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, MD. The class focused on interface design and user experience for mobile devices. Here's MICA's official class description:

In this course, explore the process for developing digital products that serve users’ needs. Students will prototype screen-based experiences that are empathetic to the needs of the end user. Students will develop design concepts that mediate relationships between people and products, environments, and services. Key concepts might include content strategy, navigation structures, usability principles, personas, and wireframes.

The class was structured around three main projects that increased in complexity begining with designing a new feature for a stock iOS app to developing an application with multiple interfaces across platforms (mobile, watch, internet of things). Rooted in theory, the class focused on looking at interface and user experience design as a lens through which all design could be judged. The syllabus, readings, and assignments can be found on the class site and below is a revised transcript of the lecture I gave on the first day.

I want this class to be a mix of practice and theory. We're going to work on three projects. Each week you'll have a research project and I'll assign a selection of readings. I don't want you to end this class just with the ability to make pretty apps or interesting interfaces. I want you to be able to defend your decisions, and rationalize design choices based on the concepts of user experience based on research, surveys, and goals.

To get started I think it's important to define some of our term and begin at the base level with the concept of the interface. Throughout this class, we're going to be focusing on the mobile phone, and for our first project the iPhone. But one of the recurring themes you'll see in this class is that interfaces are much more than that (and obviously, user experience isn't just limited to mobile apps).

My favorite definition of the interface is from Giancarlo Barbacetto. He was an italian critic who wrote a book called Design Interface in 1987.He described the interface "as whatever lies between:"

Whatever ‘lies between’ is called interface, whatever allows us to link two different elements, to reconcile them, to put them into communication.”

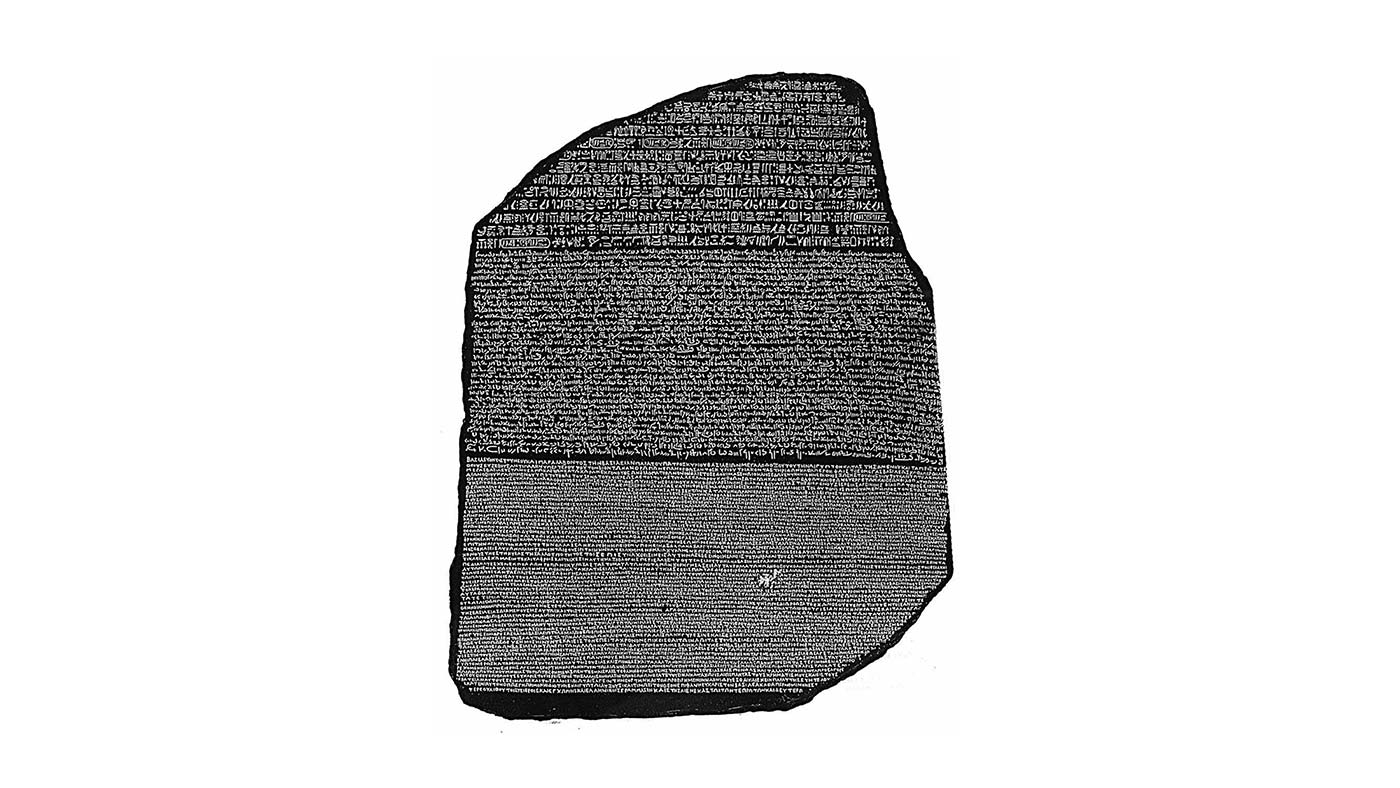

Barbacetto uses the Rosetta Stone as an example of one of the first interfaces. A shared surface which facilitates communication between otherwise irreconcilable languages and cultures.

What I think is interesting about an interface is it's always a product of its culture. It’s made in a specific time and place to be used in a specific time and place and design decisions reflect shared conventions, assumptions, and histories from that setting. An interface designed now will not necessarily work 20 years in the future. And what's exciting about thinking about designing interfaces today — in 2016 — is that we're seeing a big change in how we interact with technologies. Software is slowly replacing everything — from our watches to our cars to our thermostats.

The familiar interfaces we've known are moving to screens, and screens are usually the territory of the desigtner, so we have tremendous power in affecting how humans interact, both with machines and with each other. And very recently we're seeing interfaces that don't even have a visible element. We can talk to our computers. We can have devices in our homes that we simply speak to and they do something. You have things like Amazon's Dash buttons — which you put in your cabinets and when you're out, you just press the button and Amazon orders a new one — and the Echo, that doesn't even have a screen.

I want to come back to Barbacetto's definition. I like it because it doesn't talk about software or hardware or flat versus skeumorphic. It just says an interface puts two things in communication. In Barbacetto's definition, the Rosetta Stone is an interface. The transmission of information — of messages, of content, of language — is the interface. Which means, that a book could be considered an interface. Or a poster. Or website. Or a magazine.

I want to argue that we could say all graphic design is interface design.

And so while we'll be focusing on apps and mobile devices in this class, I want to us to consider how the principles and theories we learn over the next few weeks can be applied to your other design work. Which, of course, brings us to the most important question: what is user experience?

If you do a Google image search for user experience you get these weird diagrams these strange color wheel looking graphics:

And Wikipedia defines it as:

the overall experience of a person using a product such as a website or computer application, especially in terms of how easy or pleasing it is to use.

The emphasis there is mine because when I was in school, we were told when we were defining a word, we couldn't use the word in the definition. And this definition uses both words! It's still kind of vague.

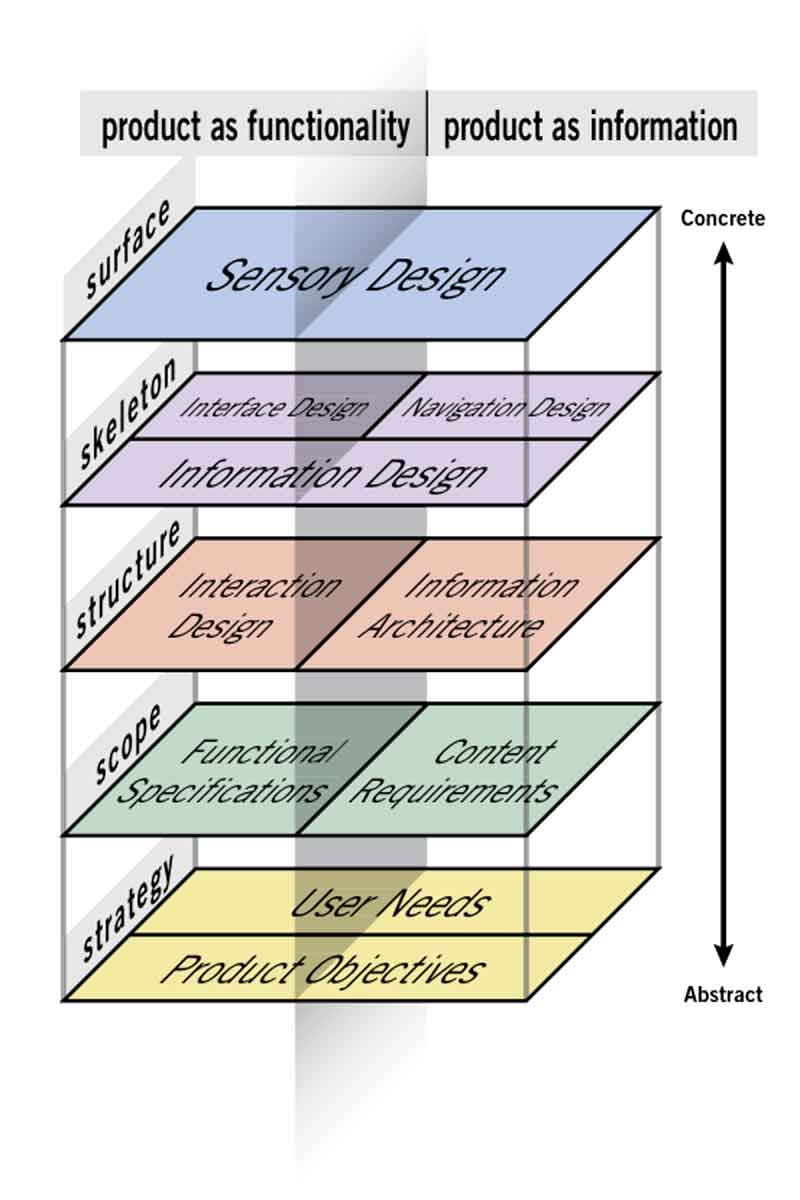

Jesse James Garrett is one of the forefathers of user experience and he developed this diagram to explain it:

Garrett puts visual design — the part we're probably most familiar with — on the top half, the latter part of the process, but there's this whole other part of the process that needs to happen before we can start designing. We need to figure out the goal of the interface, how we're going to measure it, what are the features it will have. Before we even start designing, we need to plan and account for all sorts of variables.

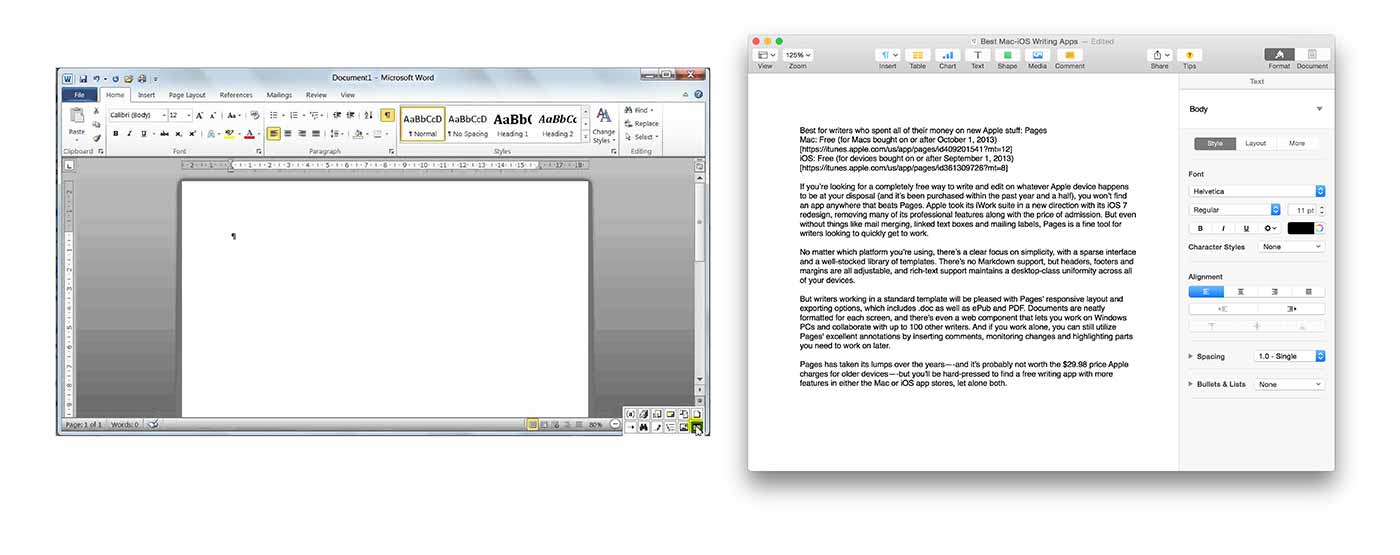

Consider the experiences of using these two apps: Microsoft Word and Apple pages:

They are both text editors, they do essentially the same thing. But the interfaces are different and therefore the user experience is different. Where Word puts a lot of features across the top, Apple hides them in slide out panels. What are the feelings you have using each app? Microsoft decided it's users want to customize their pages so they put those features right at the top. Apple thought users wanted to focus on what they were writing, so they hid everything. Neither is right or wrong, but they are after different experiences.

Here's another, non-technical example: Wal-Mart and Trader Joes.

Both sell groceries but both offer fundamental different experiences. Walk into Wal Mart and you're greeted by a nice old person. The lights are bright and all the signs are the same, shouting at you. At Trader Joes, they want to be seen as a local grocer so all their signs are handprinted. They use woods and natural materials. The cashier will ask what you're doing this weekend.The interfaces of these two stores are different, communicating different desires and fundamentally changing the user experience.

One way to think about it is user experience is branding at a personal level. It's a way to communicate the desires, messages, and mission of your company or product. Branding is about finding an audience and communicating to them — a brand is a type of interface. Think of the Apple store — probably the best retail experience today. There are no lines, they come to you when you're ready to check out. You can play with all the computers and try on an Apple Watch. Something broken? Go to the genius bar. They've designed the entire experience.

Which brings us to another question: how do you design an experience? Can you? Not really. But you can set up a framework for to help push people to the desire experience you want. As designers, we do that through:

I want to quickly talk about the differences between User Experience and User Interface. User experience deals a lot with psychology, marketing, behavior. It's about research — figuring out what competitors do and who your customers are. User Experience is works through the product structure and develops wireframes and user flows and figures out how success will be measured. User interface is focused on the literal, physical interactions. They develop branding guidelines, work on interactivity and responsiveness, and the look and feel of the app. Both of them are focused on the user and delivering the best experience to accomplish those goals through prototyping, wireframes, and user flows. The shorthand way to think about is is that the interface is the visual manifestation of the experience. They go completely hand in hand. In this class, we won't just be making nice interfaces but also thinking about user personas, researching competitors, developing prototypes and writing copy that encourages the user to do what we want them to.

There's this great quote from the design critic Max Bruinsma who said "a design today is rarely a substantive, realized product. More and more often it is a proposal, that gains its final form in the interaction with the audience, for better or for worse." He's talking about designing an interaction, designing an experience. He's talking about user experience and graphic design. Which of course means: all graphic design is about user experience. In this class, we're going to get into specifics about how think about that — from design patterns to default settings. And my hope is, as I've said before, even though we're focusing on apps, you'll see processes you can use in all your design work.