Lucille Tenazas Knows What’s Missing in Design Education

This interview was originally published in 1, 10, 100 Years of Form, Typography, and Interaction at Parsons, the book I edited for Oro Editions, and then excerpted on Eye on Design.

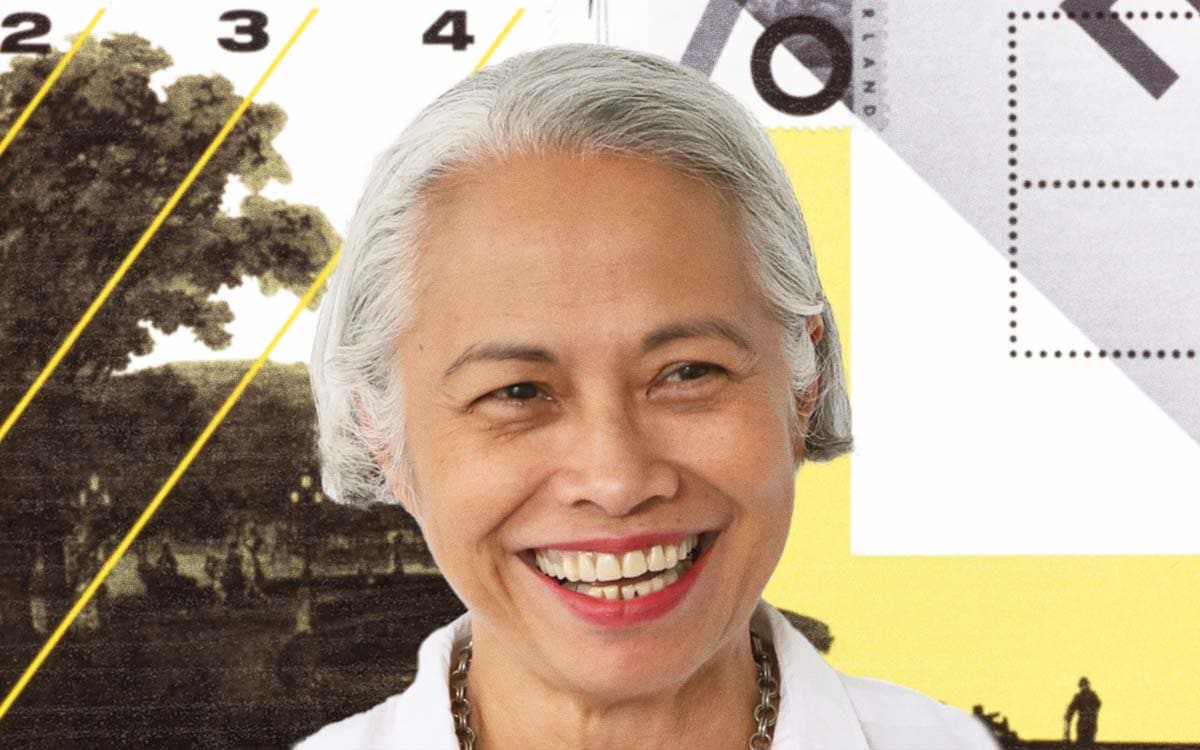

Lucille Tenazas has had a front-row seat to the evolution of design education over the last 30 years. An AIGA medalist and the 2002 recipient of the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award, she is currently the Henry Wolf Professor in the School of Art, Media, and Technology at Parsons School of Design in New York City. She previously spent 20 years in the Bay area, where she operated her own studio and was the founding chair of the MFA program in design at California College of the Arts in San Francisco. She has served as national president of AIGA, and received her MFA in design from Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Last summer, I spoke with Tenazas about her experiences in design education for the new book 1, 10, 100 Years of Form, Typography, and Interaction at Parsons, a history of the school’s Communication Design program. During our wide-ranging conversation, we talked about design as both a noun and a verb, the value of design education, and how teaching design has both stayed the same and changed over the course of her career.

The reason that I love the word design so much is that it is both a noun and a verb. Something I’ve found is that when students just start out in design, they think about it as the noun. They want to make something: the poster, the book, the app. But you’ve talked often about how teaching design is sort of like teaching a moving target; about how the field is changing so fast—the nouns are changing so fast. This makes me think it doesn’t always make sense to teach the noun, as in “here’s how you make apps” or “here’s how you bind a book.” What actually makes more sense is to teach the verb. I’m curious how you think about teaching design as a process over teaching a result?

When a student tells me, “Lucille, I have a thesis idea. I want to make a website.” I say, “No, that’s not a thesis idea.” A website is a platform, not an idea. A thesis idea is a subject that you would like to investigate further—it can be the weather, geography, traffic patterns—any topic that you’re interested in that you can explore in various ways. After exhaustive research, you can then decide what form best expresses that idea. Give me the essence of that idea, then we can talk about whether you want to do a book or a map or a website. Our smartphones are the most pervasive portals of communication we have, but how do we know what the next medium will be? Maybe there will be chips embedded in our wrists. But your brain will continue to operate as a designer. So as an educator, I ask myself, “What can I do to prepare students to think like that and ensure that they learn to be adaptable, to be observant, and to use the faculties that they have to engage with the process, and at the same time, be generous and hospitable to new forms?”

When I was a student—way ahead of you—there were no computers in the studios, but when I graduated from Cranbrook in 1982, I considered myself a designer. It’s now 2021. That’s 39 years! I have been away from school for 39 years and I am still a designer. The tools have evolved but my approach has stayed the same. The artifacts, the tools, the conditions will change based on the time, but what’s important is that one have the headspace, the tactics, the approach. I tell this to my students: It’s 2021, and if we add 40 years to that, we get to 2061. What will you be doing? I will be dead, but you’ll still be a designer! I’m proof that you can continually evolve as a designer and still be relevant, years after you have left school.

When I first started teaching, somebody older than me said that when they think about their job as an educator, they see it not necessarily to train students for that first job immediately after college, but for the one after that. That job is harder to get in some ways, because everything’s changing. And when I hear you talk about being a designer in 2061, it’s the same idea. How do you think about that long-term thinking with students who are often coming to New York, taking out loans, knowing that this is costing them money, and thinking “I better get a job after this”?

Yes, I believe in that approach and understand that attitude from the students. I think of parents who pay a lot of money for their children to be educated, and the first thing they want to know is the employability data. This is why college websites always list the companies their alumni work for, and it’s not easy to say, “don’t worry, your child has a degree in design!” But when you look at design with a capital ‘D,’ it is, as you say, both the verb and the noun; it is both process and artifact. I want to tell these parents, “your child is actually getting an education in understanding how the world works. They may end up making an artifact. That’s easiest because they’re educated in a discipline where that is a byproduct of the profession, but the bigger lesson is that they are eminently qualified to think through problems in a bigger context that maybe somebody with a business degree or a law degree will never have.”

Read the rest of the interview on Eye on Design or in 1, 10, 100 Years of Form, Typography, and Interaction at Parsons.