Graphic Design Needs a New Revolution

"Every generation needs a new revolution." —Thomas Jefferson

In the early nineties, desktop publishing dramatically changed how designers approached their work. Typesetting and pasting together comps became a thing of the past. The work began to take shape on screens. But bringing desktop publishing to the masses also induced a fear that the careers of working designers would become irrelevant. The tools of the trade were now available to all, prompting designers to rethink their own approaches.

Around the same time, a surfer-turned-designer in southern California named David Carson started designing the alternative arts and music magazine Ray Gun. Never formally trained in design, Carson used desktop publishing programs to experiment with typography and layouts that matched the irreverance of the magazine's content, including the now-famous article he set entirely in Dingbat. Looking at Carson and others' emerging style built around this freedom the computer provided, Steven Heller wrote a scathing piece for Eye Magazine titled The Cult of Ugly where he wrote this new work had a "self-indulgence that informs some of the worst experimental fine art."

However, within that "experimentatal fine art", new styles and aesthetics emerged and changed the way designers thought about their work. Along with Rick Valicenti, Rudy Vanderlans and Emigre, Carson helped introduce a generation to a new kind of expressive typography, building upon the New Wave designers that came before them. They used technology and pushed the medium forward. In a feature profile, Newsweek said Carson "changed the public face of design."

Revolutions—both technological and philosophical—are important as they turn the current system upside down. They force a rethinking of the common beliefs of the time and a challenge to move towards a better future. Desktop publishing was that type of revolution—it shook design out of the rigidity of modernism and forever changed graphic design.

Not even a decade later, the internet offered another opportunity for graphic designers to rethink their profession. Designers were no longer simply designing for print but were now tasked with designing systems that would be viewed on screens, from anywhere. A computer could no longer be viewed as simply a tool that helped designers produce work, now it was also a tool for distribution, display, and consumption. Perhaps Paul Sahre put it best in a humorously-titled talk called The Last Graphic Designer on Earth, "The computer is no longer a means to an end; now it is the end."

Designers took what they knew about designing for the page—layout, color, heirarchy, typography—and started applying that to digital spaces while introducing and discovering new methods of communication previously unknown to print designers—motion, sound, and interactivity could now be incorporated into digital work. Just like desktop publishing completely changed the way designers work, the internet did the same—once again changing the face of graphic design.

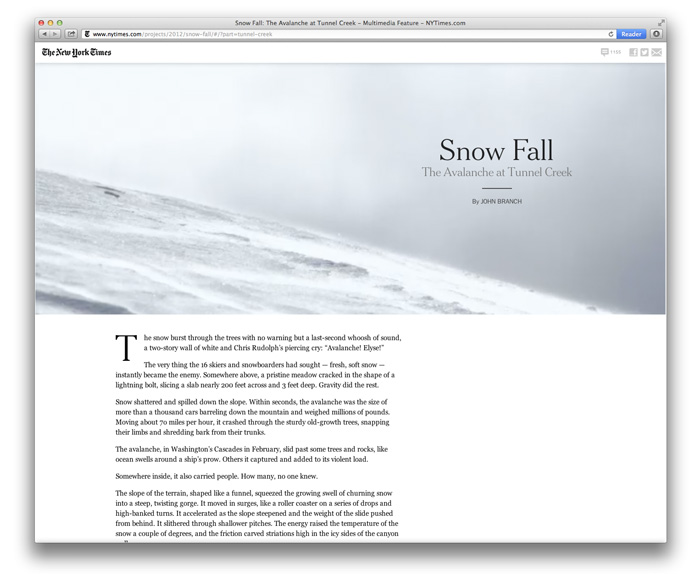

In December 2012, The New York Times published an epic, multimedia feature story called Snow Fall. Mixing text, video, photography, and sound, the piece broke from the Times' standard template to provide, as the Time's executive editor Jill Abramson called it, "a wildly new reading experience." In a letter to the newsroom, Abramson wrote, "Rarely have we been able to create a compelling destination outside the home page that was so engaging in such a short period of time on the Web."

In a digital culture where the innovative can lose its significance and popularity in a matter of days, six months later designers were still talking about Snow Fall. This, designers declared boldly, was the future of digital storytelling. To some, it had even become a verb:

"Snowfall," verb: To execute the type of expensive, time-consuming, longform-narrative multimedia storytelling that earned the Times' ambitious Snow Fall feature a Pulitzer...

It seemed like designers had another revolution before them. In August 2013, the Times released their follow-up, The Jockey, another Snow Fall-esque multimedia feature. But in a piece for Slate, Farhad Manjoo wrote that The Jockey was unreadable. The feature had too many moving elements. "I tried", he wrote, "but as soon as I scrolled down after reading the first few paragraphs, my screen was overtaken by a pointless video introduction, complete with stirring music, trumpets, and stock horseracing scenes." Manjoo continued, sounding eerily similar to Mr. Heller:

I'm all for experimentation in Web journalism. I think videos, graphics, large-format images and other extra-textual elements can improve storytelling. But I suspect that years from now, we'll look back at "Snow Fall," "The Jockey," and their copycats in the same way we now regard 1990s-era dancing hamster animations—as an example of excess, a moment when designers indulged their creativity because they now have the technical means to do so, and not because it improved the story or readers' understanding of it.

Rob Giampietro and Rudy VanderLans, in a discussion for Emigre in 2003 on Default Systems, talk of a pendulum swinging in the look of graphic design. After the dust of desktop publishing settled, designers returned once again to a conservative, minimalist aesthetic after years of over-indulging in the new technology. Looking at Snow Fall and The Jockey we can see we are in the midst of another era of overindulgance as designers wield these newfound storytelling tools.

Looking back at The Cult of Ugly ten years later, Heller appears to have softened his opinion of Carson and the post-moderists saying, "It was actually very rich ‘experimental territory'—more than today." Where is that experimentation today then? The internet transformed how designers worked a decade ago but the tools given to designers today seem to be doing little to advance the medium in ways the previous revolutions had. Snow Fall can be the sign of a new revolution in graphic design, of experimentation and pushing the boundaries of what graphic design can be.

Despite these new tools designers have at their disposal, it seems one of the most popular aesthetic designers are drawn to today is one based in nostalgia. Instead of embracing these new tools, designers are rejecting them, returning to hand-made look, inspired by vintage typographic, hand-lettering, and faux-distressing. This, of course, is not a new movement. Designers have long looked toward nostalgia as inspiration for their work. In 1991, Tibor Kalman gave a talk at an AIGA event called Good History/Bad History1 where he chided designers for abusing design history:

In the eighties and even today, in the nineties, historical reference and outright copying have been cheap and dependable substitutes for a lack of ideas. Well-executed historicism in design is nearly always seductive. The work looks good and it's hard not to like it. This isn't surprising: nostalgia is a sure bet; familiarity is infinitely comforting.

While Kalman's words were harsh and widely controversial at the time, they are perhaps truer today—two decades later—than when he spoke them. There are design books publishing work done over the last few years cribbing mid-century aesthetic. There are design blogs dedicated to faux vintage typography and digital letterpress tutorials. There is nothing inherently wrong with looking back for inspiration. The problem with nostalgia begins when it causes designers to stop looking forward. Humans gravitate towards nostalgia out of fear of an unclear future. In a world where we don't know where we're going, it's comforting to look back to familiar times. But design is about looking ahead. "What we don't seem to realize is that, culturally, much of society has moved way ahead of the designer. There was a time when things were the other way around!" wrote Dan Friedman in his essay Life, Style, and Advocacy2, "Designers and artists were visionaries leading society. I think we should aspire to do that again." Design is about imagining a future and designing the way there.

How can designers use the tools being built today to raise expectations once again and shake us out of our nostalgia? Without a revolution, graphic design can grow stale; it can stop moving forward. Where is graphic design going? What's next? Where is this generation's revolution?

Desktop publishing forced designers to look forward, and in doing so they changed the face of design. Ten years later, the internet did the same thing. Paula Scher said: "The goal of graphic design is that when it's good, it raises the expectations of what graphic design can be." The nineties had desktop publishing. The 2000s had the internet.

And this decade has its share of new tools too. We have online advancements in HTML and CSS that allow designers to produce multimedia pieces like Snow Fall. We have the rise of mobile devices and responsive web design. We have 3D printing, sustainable design, and new programming tools like Processing. Like the work of the early nineties, the pendelum has swung into overindulgance once again. As the dust settles, where will graphic design be? The tools are here. The revolution has begun. ✖

Notes

Republished in Tibor, a wonderful monograph of Tibor's work. ↩

Republished in Looking Closer: Critical Writings on Graphic Design. ↩

Special thanks to Nicole Fenton, Rory King, Kareem Shaya, and Jon Dicus for reading early versions of this essay in Editorially. It is a better piece because their invaluable feedback.